Interference (wave propagation)

In physics, interference is the addition (superposition) of two or more waves that results in a new wave pattern. Interference usually refers to the interaction of waves that are correlated or coherent with each other, either because they come from the same source or because they have the same or nearly the same frequency. Interference in physics corresponds to what in wireless communications is called multi-path propagation and fading, while the term interference has a different meaning in wireless communications.

Contents |

Theory

The principle of superposition of waves states that the resultant displacement at a point is equal to the vector sum of the displacements of different waves at that point. If a crest of a wave meets a crest of another wave at the same point then the crests interfere constructively and the resultant wave amplitude is increased. If a crest of a wave meets a trough of another wave then they interfere destructively, and the overall amplitude is decreased.

This form of interference can occur whenever a wave can propagate from a source to a destination by two or more paths of different length. Two or more sources can only be used to produce interference when there is a fixed phase relation between them, but in this case the interference generated is the same as with a single source; see Huygens' principle.

Experiments

Thomas Young's double-slit experiment shows the pattern created when two coherent beams of light interfere. The two beams have the same wavelength range and, at the center of the interference pattern, have the same phases at each wavelength as they both come from the same source.

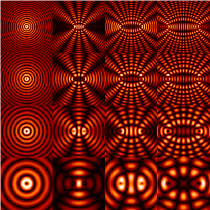

Interference patterns

For two coherent sources, the spatial separation between sources is half the wavelength times the number of nodal lines.

Light from any source can be used to obtain interference patterns, for example, Newton's rings can be produced with sunlight. However, in general white light is less suited for producing clear interference patterns, as it is a mix of a full spectrum of colours, that each have different spacing of the interference fringes. Sodium light is close to monochromatic and is thus more suitable for producing interference patterns. The most suitable is laser light because it is almost perfectly monochromatic.

Constructive and destructive interference

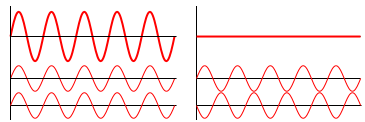

Consider two waves that are in phase, sharing the same frequency and with amplitudes A1 and A2. Their troughs and peaks line up and the resultant wave will have amplitude A = A1 + A2. This is known as constructive interference.

If the two waves are π radians, or 180°, out of phase, then one wave's crests will coincide with another wave's troughs and so will tend to cancel out. The resultant amplitude is A = |A1 − A2|. If A1 = A2, the resultant amplitude will be zero. This is known as destructive interference.

When two sinusoidal waves superimpose, the resulting waveform depends on the frequency (or wavelength) amplitude and relative phase of the two waves. If the two waves have the same amplitude A and wavelength the resultant waveform will have an amplitude between 0 and 2A depending on whether the two waves are in phase or out of phase.

| combined waveform |

|

|

| wave 1 | ||

| wave 2 | ||

| Two waves in phase | Two waves 180° out of phase |

|

Examples

A conceptually simple case of interference is a small (compared to wavelength) source – say, a small array of regularly spaced small sources (see diffraction grating).

Consider the case of a flat boundary (say, between two media with different densities or simply a flat mirror), onto which the plane wave is incident at some angle. In this case of continuous distribution of sources, constructive interference will only be in specular direction – the direction at which angle with the normal is exactly the same as the angle of incidence. Thus, this results in the law of reflection which is simply the result of constructive interference of a plane wave on a plane surface.This is true but the cancelation can be confusing

General quantum interference

| Quantum mechanics | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Uncertainty principle |

||||||||||||||||

Introduction · Mathematical formulations

|

||||||||||||||||

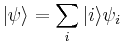

If a system is in state  its wavefunction is described in Dirac or bra-ket notation as:

its wavefunction is described in Dirac or bra-ket notation as:

where the  s specify the different quantum "alternatives" available (technically, they form an eigenvector basis) and the

s specify the different quantum "alternatives" available (technically, they form an eigenvector basis) and the  are the probability amplitude coefficients, which are complex numbers.

are the probability amplitude coefficients, which are complex numbers.

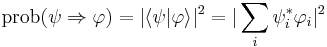

The probability of observing the system making a transition or quantum leap from state  to a new state

to a new state  is the square of the modulus of the scalar or inner product of the two states:

is the square of the modulus of the scalar or inner product of the two states:

where  (as defined above) and similarly

(as defined above) and similarly  are the coefficients of the final state of the system. * is the complex conjugate so that

are the coefficients of the final state of the system. * is the complex conjugate so that  , etc.

, etc.

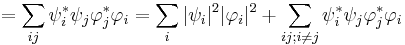

Now let's consider the situation classically and imagine that the system transited from  to

to  via an intermediate state

via an intermediate state  . Then we would classically expect the probability of the two-step transition to be the sum of all the possible intermediate steps. So we would have

. Then we would classically expect the probability of the two-step transition to be the sum of all the possible intermediate steps. So we would have

,

,

The classical and quantum derivations for the transition probability differ by the presence, in the quantum case, of the extra terms  ; these extra quantum terms represent interference between the different

; these extra quantum terms represent interference between the different  intermediate "alternatives". These are consequently known as the quantum interference terms, or cross terms. This is a purely quantum effect and is a consequence of the non-additivity of the probabilities of quantum alternatives.

intermediate "alternatives". These are consequently known as the quantum interference terms, or cross terms. This is a purely quantum effect and is a consequence of the non-additivity of the probabilities of quantum alternatives.

The interference terms vanish, via the mechanism of quantum decoherence, if the intermediate state  is measured or coupled with the environment[1][2].

is measured or coupled with the environment[1][2].

See also

- Active noise control

- Beat (acoustics)

- Coherence (physics)

- Diffraction

- Double-slit experiment

- Haidinger fringes

- Hong–Ou–Mandel effect

- Interference lithography

- Interferometer

- List of types of interferometers

- Lloyd's Mirror

- Moiré pattern

- Newton's rings

- Thin-film interference

- Optical feedback

- Retroreflector

- Inter-flow interference

- Intra-flow interference

References

- ↑ Wojciech H. Zurek, Decoherence and the transition from quantum to classical, Physics Today, 44, pp 36–44 (1991)

- ↑ Wojciech H. Zurek, Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical, Reviews of Modern Physics 2003, 75, 715 or [1]

External links

- Expressions of position and fringe spacing

- Java demonstration of interference

- Java simulation of interference of water waves 1

- Java simulation of interference of water waves 2

- Flash animations demonstrating interference

- Lissajous Curves: Interactive simulation of graphical representations of musical intervals, beats, interference, vibrating strings